Hi. Brian here. Welcome to Little Futures season 2 - a series of six emails alternating between myself and Tom. Last week: Embodied Futures. This week: Public Futures.

The chief way that innovation changes our lives is by enabling people to work for each other.

That’s from Matt Ridley’s new book, How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes In Freedom. He’s making the point that as we become more specialized we “move away from precarious self-sufficiency to safer mutual interdependence.”

I think there’s another way to read it as well.

Innovation has allowed us to merge our economic selves - professional, skilled, competitive - with our public selves - civic, social, and personal.

Innovation is revealing the publics inside companies.

The Promantic Era

How’d we get to this whole self?

One way might be that we’re soaked in context. The impact of our companies, categories, and jobs are much clearer. Analysis has entered its pulp phase. Our externalities are unavoidable.

Another is that the professional experience has shifted from documents to discourse. Decisions used to be things made in offices by a small group of people, with unresolved disagreements evaporating when the door opened. Now, discourse is the primary document of corporate life. We are now as much the way we make decisions as we are the decisions themselves. Small talk and small tensions are codified in threaded streams.

Finally, we are living in the Promantic era. Much like the Romantics gave primacy to inspiration and individualism, the Promantic era elevates the professional self across the whole self. There is no longer a separation between “professional development” and “personal development.” All skills, experiences, and practices can be brought to bear on our professional and private lives. Who we are in work is who we are.

From Public Companies to Company Publics

What does this mean for us?

Companies like to think of themselves as containers, with things like strategy, resources, and capital on the inside, and somewhere outside all that, these things called ‘publics.’

Today, at least, those containers barely hold water. At countless companies, we’ve seen employees mobilizing. Some of these carry with them more standard labor goals, but, for the most part, these are not employee concerns, they are public concerns, driven by a public self in a professional setting.

As Kit Krugman wrote earlier in the year:

“The glimmer of hope I am clinging to in trying times is that the pretending ends for good, that this global crisis liberates us from our post-industrial hangover of humans as resources, as pieces of the organizational machine, without families or feelings.”

Companies hire for aptitudes, and inherit multitudes.

Businesses compete in markets, but consist of publics.

Big Futures are for professionals. Little futures are for publics.

This week’s links are ways of thinking toward Productive Publics.

Innovation is a Publics Imperative

I’m really enjoying How Innovation Works by Matt Ridley (mentioned at the top).

This interview between Matt and Russ Roberts on EconTalk, and this one with Naval, give great overviews of the book and his thinking.

Innovation enables more productive publics.

Publics and Counterpublics

Theorist Michael Warner has written extensively about the concepts of publics and what he terms “counterpublics.” I love the idea of publics as a relation among strangers.

Publics & Counterpublics (abbreviated) by Michael Warner

A public is self-organized.

A public is a space of discourse organized by nothing other than discourse itself. [...] It exists by virtue of being addressed.A public is a relation among strangers.

The address of public speech is both personal and impersonal.

A public is constituted through mere attention

A public is the social space created by the reflexive circulation of discourse.

Publics act historically according to the temporality of their circulation.

A public is poetic world making.

Attention carries intention

Publics are tensions, whether in a company or a country, held together through the loosest of affiliations. At the very least, people must care. How do we cultivate care?

I loved this insight from David Graeber, who died earlier this month, on the role of attention and power in publics:

Feminists have long since pointed out that those on the bottom of any unequal social arrangement tend to think about, and therefore care about, those on top more than those on top think about, or care about, them. Women everywhere tend to think and know more about men's lives than men do about women, just as black people know more about white people's, employees about employers', and the poor about the rich.

And humans being the empathetic creatures that they are, knowledge leads to compassion. The rich and powerful, meanwhile, can remain oblivious and uncaring, because they can afford to. Numerous psychological studies have recently confirmed this. Those born to working-class families invariably score far better at tests of gauging others' feelings than scions of the rich, or professional classes. In a way it's hardly surprising. After all, this is what being "powerful" is largely about: not having to pay a lot of attention to what those around one are thinking and feeling. The powerful employ others to do that for them.

Productive publics require good intent. Good intent requires care. Care comes through knowledge. Knowledge accumulates through attention. Attention carries intention.

Related: This Vitalik Buterin piece on Coordination, Good and Bad.

Publishing creates Publics

I like this idea of “urgent publishing” from the Institute of Networked Culture’s Making Public project:

The urgent publishing strategies that the prototypes and methods embody and that are described in detail in Here and Now? Explorations in Urgent Publishing focus on the following key notions:

Relations between different content modules, that allow for multi-linear narratives and other (rhetorical) forms of presenting information.

Trust in the network, both of publishers who can benefit from each other’s platforms and reach, and of readers who are interested in in-depth content.

Remediation which allows publications to extend their afterlife and find readers by offering them ways to engage directly with materials.

Publics require sacrifice

Finally, a closing note from one of the great publics figures in American history, Benjamin Franklin.

Underlying productive publics is the ability to grapple with disagreement and conflict. In management, “Disagree and Commit” is the current standard frame (a management principle of encouraging disagreement in the process of making decisions, and commitment in the process of executing them).

In 1787, Ben Franklin, then 81 years old and playing the role of bridge builder, closed the Constitutional Convention with this speech on accepting faults in the service of progress.

The Opinions I have had of its Errors, I sacrifice to the Public Good. I have never whispered a Syllable of them abroad. Within these Walls they were born, and here they shall die. If every one of us in returning to our Constituents were to report the Objections he has had to it, and use his Influence to gain Partisan in support of them, we might prevent its being generally received, and thereby lose all the salutary Effects and great Advantages resulting naturally in our favour among foreign Nations, as well as among ourselves, from our real or apparent Unanimity. Much of the Strength and Efficiency of any Government, in procuring and securing Happiness to the People depends on Opinion, on the general Opinion of the Goodness of that Government as well as of the Wisdom and Integrity of its Governors. I hope therefore that for our own Sakes, as a Part of the People, and for the sake of our Posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution, wherever our Influence may extend, and turn our future Thoughts and Endeavours to the Means of having it well administered.

The opinions I have had of its errors, I sacrifice to the public good.

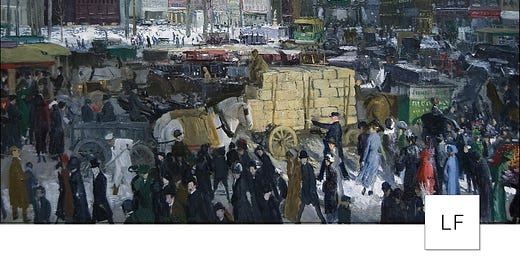

Today’s artwork: George Bellows, "New York, 1911".Before the Big Future, endless little futures…